Contact Sue Dyson at sue.dyson@aol.com

For new, views, and exclusive deals, subscribe to The Horse Physio’s free newsletter.

If you prefer to watch or listen, please click on the video above. If you prefer to read, please keep scrolling.

There are many misconceptions in the equine world, one of which surrounds horses that behave normally in hand and on the lunge but perform sub-optimally when ridden or behave ‘badly’ – and sometimes get labelled as naughty horses. If thought is given that an underlying cause may be pain, there is often an assumption that because this behaviour is only seen when ridden and since the change is a rider sitting on the horse’s back it must reflect primary back pain.

This is too simplistic a view. Carrying tack and a rider results in many changes to a horse, with increased loading not only of the back but also of the forelimbs and hindlimbs. Head and neck carriage alters and this also influences limb loading. We know that there are many horses which appear non-lame in hand or on the lunge but are lame when ridden. This is usually a reflection of primary pain in one or more limbs.

Horses are prey animals and are remarkably stoical individuals which try to mask pain. They do this in a variety of ways in the face of forelimb or hindlimb lameness, including reducing the range of motion of the back (‘stiffening’ the back), taking shorter steps, reducing the height of arc of foot flight and increasing the proportion of time each limb stays on the ground during each stride. Long term stiffening of the back can result in abnormal tension in the long muscles of the back, with or without muscle pain, most particularly in the lumbar region, the area behind the saddle. The muscles may fail to develop properly or may lose bulk through lack of normal use.

The potential influence of an ill-fitting saddle cannot be over-emphasised. A saddle which does not fit the horse can have an enormous influence on a horse’s freedom of movement, head and neck carriage and step length. It can also influence back muscle function and development particularly underneath the saddle. Concavities in the muscles under the front of a saddle are a hallmark of a chronically ill-fitting saddle. A saddle which does not fit a rider has the potential to adversely influence the rider’s weight distribution and the forces transmitted to a horse’s back. Overload of the back one-third of the saddle, in particular, will result in adaptations of a horse’s gait and increase the chance of back pain, especially under the back of the saddle (the caudal thoracic region) and the lumbar region.

For new, views, and exclusive deals, subscribe to The Horse Physio’s free newsletter.

Many horses with no clinical signs of back discomfort that are performing normally have two or more close or impinging spinous processes in the thoracolumbar region. The radiological (x-ray) identification of impinging spinous processes does not equate with pain causing poor performance. Horses with short back conformation are more likely to have close or impinging spinous processes than horses with long back conformation, and Thoroughbreds are predisposed. The clinical features associated with impinging spinous processes are non-specific and it is generally not possible by clinical assessment alone to determine the potential role of close spinous processes to a horse’s performance problems.

The images below are of a 6-year-old Warmblood gelding with progressive difficulties in behaviour when ridden: head in the air, very tense, reluctant to go into canter; changed legs behind in canter; teeth grinding; more recently bucking in canter. No overt lameness was seen, but the horse was more tense in trot when the rider sat on the right hind/left front diagonal compared with the opposite diagonal. There was a short stepping hindlimb gait, but this is an inevitable consequence of the high head and neck carriage. The horse ‘hung’ on the left rein.

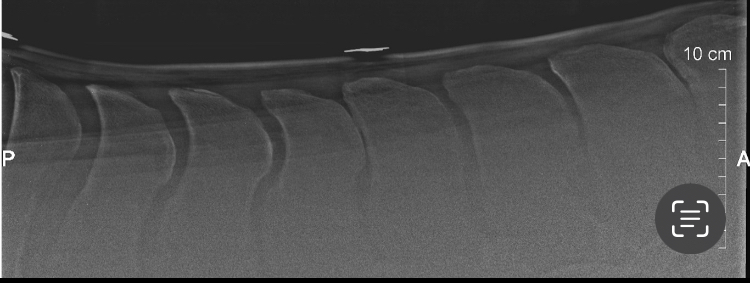

Radiograph of the spinous processes of the twelfth thoracic (T12) to first lumbar (L1) vertebrae. The spinous processes of T15 and 16 and T18 and L1 are impinging.

There was no change in the horse’s performance when local anaesthetic solution was infiltrated around the impinging spinous processes. This indicated that the radiological findings were of NO clinical significance. The horse’s ridden performance was dramatically improved when pain was removed from the top of the suspensory ligaments of each hindlimb. Bilateral hindlimb proximal suspensory desmopathy was the primary cause of poor ridden performance.

A horse with close spinous processes that is ridden poorly, with failure to recruit core muscles, and a tendency to work with the head and neck elevated and the back extended (dipped) is more likely to develop associated clinical signs than a horse which is worked ‘on the bit’, with good hindlimb impulsion and engagement and recruitment of key core muscles.

It is true to say that the larger the number of spinous processes that are close or impinging and the greater the degree of secondary bony change (bone proliferation or bone destruction) the greater likelihood is that there may be associated discomfort. However, before jumping to conclusions that these impinging spinous processes (so-called kissing spines) are the primary cause of poor performance it is vitally important that a comprehensive clinical assessment is made of the entire horse, the tack and the rider, to rule out other potential factors. Moreover, the horse should be evaluated ridden, and the effect of local anaesthetic solution infiltrated around the spinous processes assessed. If impinging spinous processes are the primary problem, then there should be a dramatic improvement in the horse’s ridden performance.

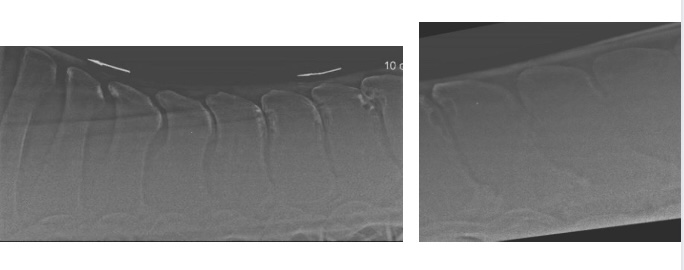

Radiographs of the spinous processes of the 11th thoracic (T11) to3rd lumbar (L3) vertebrae. There is impingement of the spinous processes of T15 to L1, with secondary bony changes seen as regions of increased whiteness or blackness of the bone. This horse was used for horse ball and had developed dangerous bucking behaviour which was abolished when local anaesthetic solution was infiltrated around the close spinous processes.

Take home messages:

Copyright Sue Dyson

For new, views, and exclusive deals, subscribe to The Horse Physio’s free newsletter.

Sue Palmer MCSP, aka The Horse Physio, is an award-winning author, educator, and Chartered Physiotherapist. Sue specialises in understanding the links between equine pain and behaviour, focusing on prevention, partnership and performance. She promotes the kind and fair treatment of horses through empathetic education, and is registered with the RAMP, the ACPAT, the IHA, the CSP and the HCPC.

You can find The Horse Physio on the web, on Facebook, on Instagram, and on YouTube, book an online consultation, or take a look at Sue’s online courses.

Horse Health Check: The 10-Point Plan for Physical Wellness

Head to Hoof: An Introduction to Horse Massage

Horse Massage for Horse Owners

Stretching Your Horse: A Guide to Keeping Your Equine Friend Happy and Healthy

Books

Harmonious Horsemanship, co-authored with Dr Sue Dyson

Understanding Horse Performance: Brain, Pain or Training?

Horse Massage for Horse Owners

Thank you

Thank you for your interest in this post; I appreciate your time and am grateful you chose to spend it with me. If you found value in this article, please support me by liking, subscribing, following, and sharing it on your favourite social media platform, and turn on the relevant notifications for future content from The Horse Physio. Please also take a moment to subscribe to my newsletter. Your support means the world to me, and it helps me continue creating content that matters to you.